While this article was written for the UK, statistics for girls with depression are similar in the US. We need to do more to protect our children.

Data from government-funded research prompts fresh questions about effect of social media and school stresses on young people’s mental health.

One in four girls is clinically depressed by the time they turn 14, according to research that has sparked new fears that Britain’s teenagers are suffering from an epidemic of poor mental health.

A government-funded study has found that 24% of 14-year-old girls and 9% of boys the same age have depression. Their symptoms include feeling miserable, tired and lonely and hating themselves.

That means that about 166,000 girls and 67,000 boys of that age across the UK are depressed.

The findings are based on how more than 10,000 young people that age described how they were feeling. The data has prompted fresh questions about how social media, body image issues and school-related stresses affect young people’s mental welfare.

It also strongly suggests that being from a low-income family increases the risk of depression and that ethnicity is potentially a key factor too.

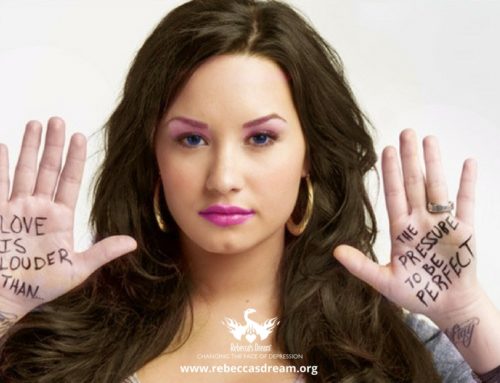

“We know that teenage girls face a huge range of pressures, including stress at school, body image issues, bullying, and the pressure created by social media,” said Marc Bush, the chief policy adviser at the charity Young Minds. “Difficult experiences in childhood – including bereavement, domestic violence or neglect – can also have a serious impact, often several years down the line.”

Dr Praveetha Patalay, the lead author of the research, said the findings revealed “worryingly high rates of depression” among 14-year-old girls and the “increasing mental health difficulties faced by girls today compared to previous generations”.

The study was undertaken by academics from University College London and the University of Liverpool and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. No reliable studies exist into previous prevalence of depression among UK teenagers. They found that between the ages of three and 11 small but growing proportions of boys and girls – up to around 10% – suffered from emotional problems such as feeling depressed and anxious, as reported by their parents.

However, while the prevalence of such problems remained constant among boys between the ages of 11 and 14, it rose from 12% to 18% among girls, again based on accounts submitted by their parents.

But when 14-year-old boys and girls themselves were asked about their mental health, far more girls – 24% – disclosed that they were feeling depressed than the 18% whose parents said they were.

The findings may suggest that parents underestimate the extent of, or fail to pick up on the signs of, depression among girls up to the age of 14 but overestimate how common the condition is among boys that age.

“At age 14, when children reported their own symptoms, 24% of girls and 9% of boys were suffering from high symptoms of depression,” according to the academics’ summary of their findings.

That was based on the number of girls who answered “true” or “sometimes” when asked 13 questions including if, in the previous fortnight, “I felt miserable or unhappy”, “I cried a lot”, “I felt I was no good anymore” or “I thought nobody loved me”. Other statements that they indicated did or did not apply to them included “I hated myself”, “I felt lonely”, “I was a bad person” and “I thought I could never be as good as other kids.”

The study concludes that, given the high number of 14-year-old girls deemed to be depressed based on their responses to those questions: “This suggests that levels of depression among today’s teenage girls are high.”

Anna Feuchtwang, chief executive of the National Children’s Bureau, which also collaborated on the research, said: “We now have the strongest evidence yet that a huge number of young people are depressed. Many more are unhappy. Children are facing huge pressures.”

Among 14-year-old girls, those from mixed race (28.6%) and white (25.2%) backgrounds were most likely to be depressed, with those from black African (9.7%) and Bangladeshi (15.4%) families the least likely to suffer from it.

Girls that age from the second lowest fifth of the population, based on family income, were most likely to be depressed (29.4%), while those from the highest quintile were the least likely (19.8%).

Bush, of Young Minds, said: “To make matters worse, it can be extremely difficult for teenagers to get the right support if they’re struggling to cope. [And] we need to rebalance our education system, so that schools are able to prioritise wellbeing and not just exam results.”

Janet Davies, chief executive of the Royal College of Nursing, said a fall in the number of school nurses was making it harder to identify young people with mental health problems. “Demand for adolescent mental health services is reaching new heights but the NHS is failing young people,” she said.

Theresa May has made young people’s mental health one of her top priorities and a government green paper is due soon.

Mental health care for under-18s is increasing, according to NHS England. “NHS services for children and young people are expanding at their fastest rate in a decade,” a spokesperson said. “This year the NHS will treat an additional 30,000 children and young people, supported by an additional £280m of funding.”

Source > The Guardian